By Jim Moore, OD, MBA

SYNOPSIS

Do you know your relevant costs? Understanding this basic business management concept can help you make gooddecisions oncritical practice-growth issues.

ACTION POINTS

CALCULATE OPPORTUNITY. Compare all related costs of business opportunities before deciding which one(s) to pursue.

AVOID UNCALCULATED EXPENSES. This will allow you to avoid making decisions based on a false representation of potential.

APPLY RELEVANT COSTS. Doing so will enable you to make accurate financial decisions–understanding how all costs related to the opportunity affect profitability.

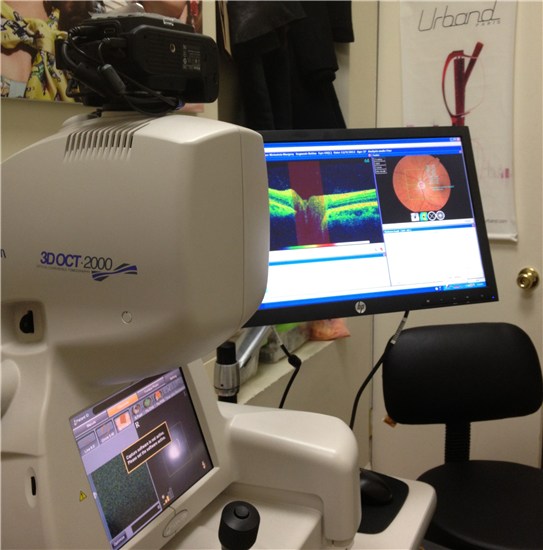

Assess relevant costs before investing in instrumentation like an OCT

When optometrists invest in goods such as office furniture, frames, contact lenses and diagnostic instrumentation, a common mistake is under-estimating, or misunderstanding, the costs related to these purchases. You can more easily gauge the costs that you will incur from your purchases by understanding the concept of relevant costs.

Relevant costs are costs that will affect future expenses and revenue. Irrelevant costs have already been incurred and will have no bearing on future expenses or revenue. Opportunity costs are the value of the best opportunities forgone while sunk costs have already been incurred, cannot affect future costs and cannot be changed by any current or future actions. Here is an example of a recent purchase my family made that underscores the value of understanding relevant costs.

As the former owner of an independent practice, which I opened cold over 10 years ago, and profitably sold in 2011, I saw first-hand how important understanding relevant costs is to improving an optometric practice’s profitability. The concept of relevant costs was further solidified for me last year while earning my MBA.

Two years ago, my family (or was it only me?) purchased a brand new boat. It’s brilliant sparkling white gel coat with sea blue striping, perfectly polished stainless steel railings, and a 150 horsepower 4 stroke engine called to me. I envisioned the endless summer days on the water of the beautiful Puget Sound cruising and fishing till sunset. Oh what fun our family will have! And we did have fun…especially the first 30 minutes or so. After that, my kids seemed to prefer any other activity as long as it was on land!

Fast forward two years, and after only a handful of days and hours on the water, I have decided to sell the boat. But how much should I sell for? Let’s make up some numbers: Assume I financed the purchase price of the boat ($25,000 – $5,000 deposit) $20,000 for seven years at 4 percent interest = $275 /month. Now after two years, I still owe $15,000. I research online and find a private party sale price of $19,000. If I can sell for $20,000, I can recoup the $5,000 I put down but still be out the money I have paid over the past two years. What is my opportunity cost?

CALCULATE OPPORTUNITY

An opportunity cost is defined as the value of the best alternative foregone. The best alternative foregone is basically the best opportunity presented which you do not accept. It is not necessary for the business decision making process to calculate the opportunity cost of every situation, only the best. Let’s say I have two offers to sell the boat; one offer is for $19,000 and the next offer is for $20,000, and I decide NOT to accept either offer. The opportunity cost is calculated using the $20,000 offer since it was the best alternative forgone. Now to calculate the opportunity cost; I have an offer for $20,000 and choose not to accept, my opportunity cost is $5,000 PLUS the $275 monthly payment I will no longer have to make. Remember I still owe $15,000 which is a monthly payment of $275 so the $20,000 offer less $15,000 still owed=$5,000 cash plus the monthly payment. If the best offer I receive is for only $15,000 then my opportunity cost if I do not accept this alternative is the monthly payment of $275 I will no longer have to make since that $15,000 will be used to pay off the note.

Studies show that people tend to ignore or tone down the impact of opportunity costs. One study asked people if they would pay $500 for two Super Bowl tickets. Most said they would not. Many of those same people said they would not sell the Super Bowl tickets for $500 if they were given the tickets at no cost. These people refused to incur the $500 out-of-pocket costs of buying the tickets but were willing to incur the $500 opportunity cost by going to the game instead of selling the tickets. Behavior such as this is economically inconsistent and ignoring or downplaying the importance of opportunity costs can result in inconsistent and faulty business decisions.1

AVOID UNCALCULATED EXPENSES

In the boat example, what about the $10,000 ($25,000 original sales price -$15,000 sold price) I just loss? That is a sunk cost. Sunk costs are costs that have been incurred in the past, do not affect future costs and cannot be changed by any current or future actions. Sunk costs are irrelevant in your business decision-making process. People tend to focus an inappropriate amount of attention to sunk costs. Future decisions need to be based on future costs.

Opportunity and sunk costs are just two classifications of many costs: Fixed and variable (as well as step-fixed, step-variable, semi-variable or mixed), controllable and uncontrollable, direct and indirect, differential, marginal and average.

APPLY RELEVANT COSTS

To use a more clinically relevant example, I had the experience of purchasing a whiz bang piece of equipment–a GDx–at the exhibit hall of a conference. A year later, I was not using the piece of equipment as expected and was contemplating selling. I paid $15,000 cash and thought I could perhaps sell for $10,000. If I had an offer for $8,000, what is my opportunity cost? Yes, $8,000. The $15,000 spent is a sunk cost and is irrelevant in my decision to sell or at what price to sell.

Another example is inventory. After a few slow quarters, my accountant recommended a frame sale to boost cash flow. He wasn’t only suggesting a measly 20 percent off sale either. He was suggesting an aggressive 50-75 percent discount. I couldn’t get over how much money I had spent on the frame inventory and wouldn’t allow a discount of more than 30 percent. Any more than that and I would be “losing” money. What I failed to realize was that money spent on the frame inventory was already lost being a sunk cost and irrelevant in my decision as to how much to discount the frames.

I had a finance professor who used automobile dealerships as an example and referred to their inventory of cars as “piles of cash” sitting in the parking lot. The dealer had already paid a certain amount of money for that car you are eyeing and that cost is sunk. Any amount of money you offer is an “opportunity” for them. Much like the frame inventory, or “pile of cash” hanging on your wall, any amount of money you can generate from a sale is an opportunity. If a sale will increase your revenue an additional $1,000 for that day over the revenue generated by not having a sale, that $1,000 is your opportunity cost, irrelevant of how much you may have spent on your frame inventory.

Another relevant cost, the marginal cost is a concept that when understood can also aid in your decision making. The marginal cost is the extra cost when one more unit is produced. To use eye exams as an example, after rent, staff and all other expenses involved with being able to see one patient, the marginal cost to see one more patient causes the marginal cost to decrease. Let’s assume I have just examined my 15th patient of the day. There were costs associated with seeing those 15 patients and the additional costs for seeing the 16th would be the marginal costs. Evaluating the marginal costs, and therefore, additional profit potential for one more unit will aid in situation analysis.

Of course, there are other factors to consider in these simplified examples such as revenue generated from lenses sold in addition to the frames, lab costs, employee costs, utilities and space associated with equipment usage, additional services generated, perceptions of quality care, etc… And even though certain costs are by definition irrelevant, that’s not to say I won’t learn from the $10,000 sunk cost the next time I am strolling around a marina or exhibit hall. A clear understanding of relevant costs will aid in your future decision making abilities.

1. Hilton, Ronald W., Managerial Accounting, Creating Value in a Dynamic Business Environment, 9th edition.

Related ROB Articles

Advice for New and Experienced ODs: Understand Essential Business Concepts

Practice By the Numbers: Track Your Key Expenses

Instrumentation Budgeting: Calculate ROI–and Profit Potential

Jim Moore, OD, MBA is the former owner of an independent practice in Loveland, Co, which he profitably sold in 2011. He now works as an OD on a part-time, contract basis, in Silverdale, Wash . To contact him: moore.jim98@gmail.com

Jim Moore, OD, MBA is the former owner of an independent practice in Loveland, Co, which he profitably sold in 2011. He now works as an OD on a part-time, contract basis, in Silverdale, Wash . To contact him: moore.jim98@gmail.com