By Eric R. Ritchey, OD, PhD, FAAO

This is the third in a series of excerpts from the newly posted ROB Special Report “Opportunities & Business Strategies in Myopia Management.” CLICK HERE to download the full report, which is sponsored by Alcon, CareCredit and Essilor.

>>Click HERE to explore the new publication Review of Myopia Management>>

It’s an exciting time in myopia management, with many new and enhanced treatments available to your patients.

Traditionally, optometry has managed myopia from a palliative approach, treating symptoms with spectacles and contact lenses while offering little in the way of a true treatment.

The advent of refractive surgery offered patients an alternative to spectacles and contact lenses; however, this option did nothing to prevent the development of ocular disease associated with increased ocular growth. While myopia prevalence has been steadily increasing for over 40 years, our understanding of refractive error development and myopia progression have also increased.1-3

New Resource

Today’s optometrist can finally offer our young myopes an alternative to traditional refractive error correction that can improve their quality of life and reduce their potential for future ocular disease.

Today’s practitioners also have diagnostic tools at their disposal to effectively track the progression of myopia and determine if their treatment method is effective. In this article, we will discuss some of the technologies available to eyecare practitioners for the modern management of myopia.

First, we need to address the question of why we should attempt to slow myopia progression. Often the parents of potential patients do not feel that being nearsighted is a significant health concern. While most patients consider myopia to be a nuisance, or a relatively benign condition, myopia has become a worldwide epidemic.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that the prevalence of myopia has been steadily increasing globally, with some countries in Southeast Asia reporting myopia prevalence of 90 percent or greater in young adults by the time they enter their twenties.4-6 The U.S. and Europe, while not seeing increases as large as those seen in Asia, have also shown a steady increase in myopia development.1, 7, 8

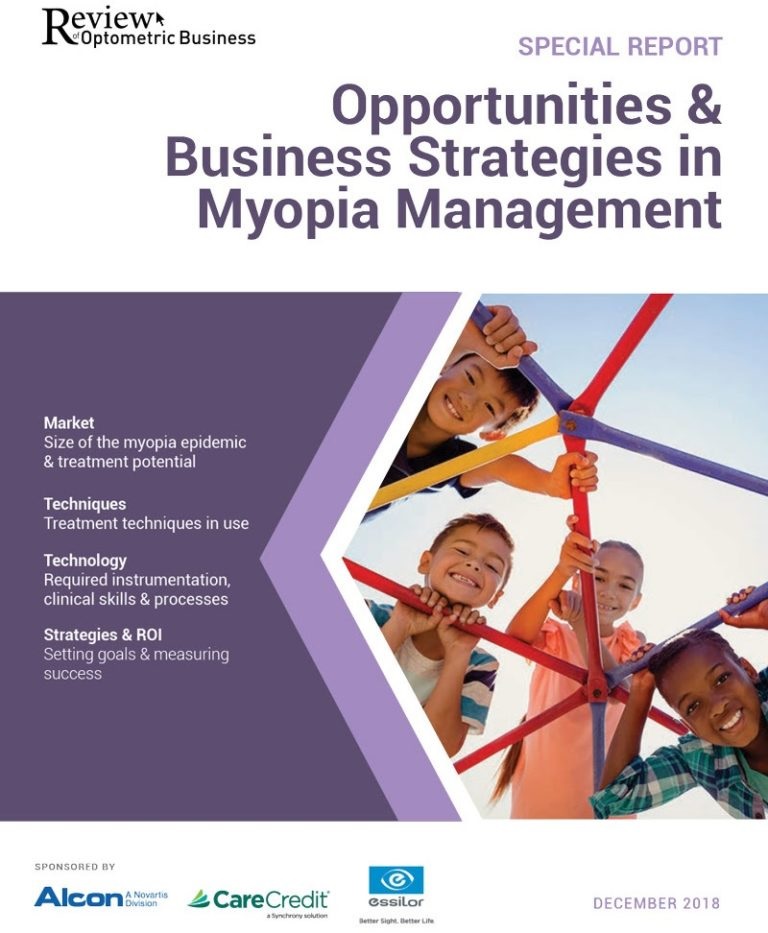

Along with the increase in myopia prevalence, the age of myopia onset is decreasing, meaning that the myopes we see in the future will most likely be more myopic than our current patients. The consequence of these changes is the development of future disease and a lower quality of life for our patients. Myopia has been associated with a number of conditions, including increased odds for developing cataracts, open angle glaucoma and retinal detachment.

Other Pieces to Explore

High myopia, defined as worse than -5.00 or -6.00 diopters of myopia in most scientific publications, is associated with a number of conditions including posterior staphyloma, chorioretinal and RPE atrophy and lacquer cracks. Most significant may be the development of myopic maculopathy, which includes macular hemorrhages, foveoschisis, macular holes and choroidal neovascularization (CNV). These conditions may lead to significant vision loss or blindness.9-16

With an increasing number of myopic patients and more myopia-related ocular disease, myopia will become an increasingly significant financial burden on public health infrastructure, not only from the cost of spectacles and contact lenses, but, also from the increased medical and surgical expenses associated with treating high myopia.17-20

Given these risks, the case for attempting to slow myopia progression is compelling. However, it is important to remember that currently there is no FDA-approved pharmacological or medical device treatment for the prevention of myopia development or for the slowing on myopia progression. All of the technologies we will discuss are used on an “off-label” basis. Off-label usage of medical devices and pharmaceuticals is a common and accepted practice in health care.

Per the FDA: “Good medical practice and the best interests of the patient require that physicians use legally available drugs, biologics and devices according to their best knowledge and judgement. If physicians use a product for an indication not in the approved labeling, they have the responsibility to be well informed about the product, to base its use on firm scientific rationale and on sound medical evidence, and to maintain records of the product’s use and effects.”

Given this, patients who wish to pursue myopia control treatment should be educated that use of any of these technologies is off-label. The risk and benefit from use of such treatment, and this education, should be documented in the patient record.

>>CLICK HERE TO EXPLORE REVIEW OF MYOPIA MANAGEMENT>>

References

1. Flitcroft, D. I. (2012). The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Progress in retinal and eye

research, 31(6), 622-660.

2. Vongphanit, J., Mitchell, P., & Wang, J. J. (2002). Prevalence and progression of myopic retinopathy in an older population. Ophthalmology,

109(4), 704-711.

3. Ogawa, A., & Tanaka, M. (1988). The relationship between refractive errors and retinal detachment–analysis of 1,166 retinal detachment

cases. Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology, 32(3), 310-315.

4. Lim, R., Mitchell, P., & Cumming, R. G. (1999). Refractive associations with cataract: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Investigative

Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 40(12), 3021-3026.

Eric R. Ritchey, OD, PhD, FAAO, is Assistant Professor at The University of Houston College of Optometry.

Eric R. Ritchey, OD, PhD, FAAO, is Assistant Professor at The University of Houston College of Optometry.