By Jennifer Jabaley, OD

July 25, 2018

Many of us aspire to create great practices, but we often fall short, attaining good, but not quite great. A book I recently came across has given me ideas for getting to the next level of excellence as a doctor and practice leader.

Recently I attended an optometry convention where I met many new colleagues. In general, most were midlife, in the midst of raising families and managing practices, and the general consensus was that life was good. Then I chatted with a well-known practice management consultant, and it was clear for him, life was great. Why, I wondered, do so few make that final leap? Could good be the enemy of great? Is it just too easy to settle for a good family and a good practice and never make that rise out of mediocrity?

What if that’s not enough? What if we want to catapult to the next level of success? What steps should we take?

I began to research. At my local library I found a book by Jim Collins, “GOOD TO GREAT: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…And Others Don’t.” The book was published over a decade ago, but I found this title most appropriate to my inquiries, namely because not only did it research common characteristics shared by companies that made the transition from good to great, but it compared and contrasted organizations within the same field.

For example, Collins highlighted the story of two drugstores, Walgreens and Eckerd. In the mid-1970s, both chain stores were roughly the same size, the same industry, and yet, Walgreens climbed and soared with success while Eckerd faltered and faded. I found this to be unique for a book on business development, and thought it would help me find clues for success within the field of optometry.

Additionally, while analyzing similar industry successes and failures, Collins concluded that these businesses became great not by being in the right industry at the right time, nor through exceptional geographical location, but rather what made them prosperous was their culture of effort and enterprise.

So, if we remove factors like urban versus suburban versus rural settings, discount geographical location, competition and demographics, and put all optometry practices on the same playing field, what then are the forces that cultivate that culture of effort and enterprise? What will make us rise from good to great?

Collins outlines simple concepts that disguise their power and effectiveness. The basis of making the transition from good to great comes down to three key areas:

DISCIPLINE PEOPLE

Good-to-great executives didn’t first plot vision, strategy and mission statements, and then get people committed to the new direction. Instead, these leaders first got the right people on the bus – and equally important, they got the wrong people off the bus – and then they figured out where to drive it. These leaders understood that if you begin with who, rather than what, you can more easily adapt. Once you have the right people on the bus, the huge problem of motivating and managing your staff diminishes.

The right people don’t need to be tightly managed; they are self-motivated with inner drive and want to be part of something great. To be clear, the main point is not just about assembling the correct team for your practice – that’s not a new concept. What was interesting and groundbreaking was the idea of getting the right staff in place before you decide to make any other major changes.

In comparing and contrasting the successful companies to those that floundered, again and again Collins found that the idea of a great, genius leader with a vision and an array of staff rarely transitioned from good to great. It was the humble, collaborative leaders who focused on assembling a team, and then drove the bus where the companies wanted to go, that broke out.

DISCIPLINED THOUGHT

Collins highlighted that successful companies follow what he calls The Hedgehog Concept.

In Isaiah Berlin’s famous essay, “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” he divides the world into hedgehogs and foxes based on an ancient Greek parable: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

The fox is cunning, crafty and has complex strategies. The hedgehog, on the other hand, simply waddles along with slow purpose. Collins extrapolates from this parable to divide people into two basic groups: foxes and hedgehogs. Foxes pursue many goals at the same time. They are scattered and diffused. Hedgehogs, on the other hand, simplify a complex world into a basic concept that unifies and guides everything. Hedgehogs see what is essential and ignore the rest.

How does this pertain to a successful business?

Those companies that rose from good to great were hedgehogs. They gained a clarifying idea that skyrocketed them past companies that were scattered, diffused and inconsistent.

Consider Walgreens versus Eckerd. Both companies were in the same industry, and yet Walgreens made a critical hedgehog decision: To dominate one niche. Walgreens decided it would be the most convenient drugstore. It would not be the cheapest, not the prettiest; it would be the most convenient. So they began to position themselves in prime real estate and altered their hours. They dropped all other metrics and focused solely on the one, singular idea: convenience. And it worked.

How do we find our one great niche? How do we find what is going to set our practice apart from all others?

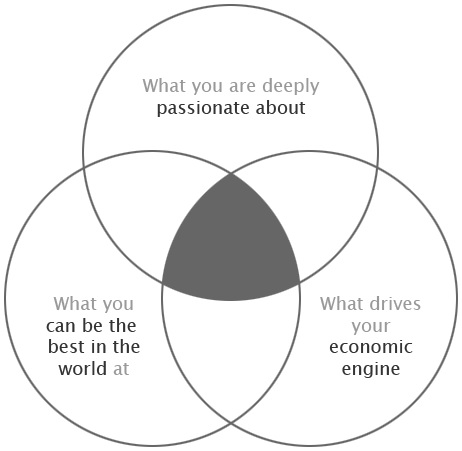

Colin proposes a three-circle model to test for greatness.

The first circle asks, what can you be the best at? This involves a realistic appreciation of your abilities. If your practice is in a rural setting without an abundance of ophthalmology nearby, you may want to become a niche medical optometric practice. But is that realistic? Would you be willing to take extra continuing education to educate yourself? Would you be willing to buy additional equipment and align yourself with this goal? If something is truly going to become a niche market, you cannot just be competent at it, you must excel.

The second circle asks, what drives your economic engine? Where exactly is the abundance of your profit coming from? Or, can you effectively predict where you can sustain robust cash flow and profitability? For example, if you live in an affluent area where parents are routinely shelling out gobs of cash for private batting lessons for their children, agility training and insane travel ball fees, perhaps a sports vision niche would become the economic engine that propels your practice to greatness.

The third circle asks, what is your passion? The good-to-great companies focused on activities that ignited their passions. If you hate sports, no matter how great an opportunity, you will never truly succeed at a sports vision niche. However, if you are a high myope, you may have personal experience to drive passion for a myopia-control practice. If you are someone who appreciates great service at a restaurant, or shopping excursion, perhaps your passion is service. You can make your niche market the practice that remembers what magazine each patient likes to read, what beverage they prefer while they wait.

To have a fully developed Hedgehog Concept, you need all three circles: talent, passion, economic engine.

DISCIPLINED ACTION

The final concept in the model of good to great is a culture of disciplined action. After hiring the right staff, identifying talent, passion, economic engine and focusing on a niche market, the biggest stumbling block became an unwieldy ball of disorganization. Many companies profiled by Collins lacked planning, accounting and systems, and eventually problems rose to the surface.

Collins suggests aligning two complementary forces together – a culture of discipline with an ethic of entrepreneurship to find the magical alchemy of superior performance and sustained results. In other words, your team should have simultaneous freedom and responsibility.

If you have the right people on the bus, they shouldn’t need to be micromanaged. They shouldn’t need forced motivation because they are already aligned with the practice goals.

In conclusion, Collins says that going from good to great comes down to a culture of discipline. It starts with disciplined people – not by getting the wrong people to behave correctly, but getting self-disciplined people in the first place.

Next, disciplined thought to understand and find your personal hedgehog concept or niche market. Finally, disciplined action to execute goals.

The order of this, according to Collins, is the crucial step many businesses fail to take. Everyone would like to be the best, but most practices lack the clarity to figure out how to make that potential a reality. Discipline alone will not produce results. But this framework and timeline will break out your practice from good to great.

Have you taken your practice from good to great? How did you do it, or, if you haven’t done it yet, how are you planning to do it?

Jennifer Jabaley, OD, is a partner with Jabaley Eye Care in Blue Ridge, Ga. To contact her: jabaleyjennifer@yahoo.com

Jennifer Jabaley, OD, is a partner with Jabaley Eye Care in Blue Ridge, Ga. To contact her: jabaleyjennifer@yahoo.com